"I tried Grammarly's plagiarism checker free of charge because even if it was best of lines, it was the worst of lines if someone else already wrote it."

~~~*~~~*~~~

In writing a book, you have to decide on the perspective. Will it be first person ("I clipped the red wire.") or third person ("Tony clipped the red wire.")? Omniscient or limited? Present or past tense?

If you have ever seen agents or writing pundits discuss perspectives in writing, one thing which is utterly verbotten is head-hopping. Just as it sounds, that's the practice of having the perspective hop from head to head, where you get an insider's view of the thoughts and knowledge of different people in a scene.

For example:

"Tony clipped the red wire, knowing it would defuse the bomb. Uma's heart thrilled at his masterful wielding of the knife and she knew that he was the man of her dreams."See how the second sentence tells us what Uma was thinking? Although this kind of writing was once common, modern sages of the pen eschew such constructions. The above passage would be rewritten to avoid head-hopping, limiting the knowledge to only those things the main character could know or see:

"Tony clipped the red wire, knowing it would defuse the bomb. Uma gasped at his masterful wielding of the knife. In that moment, Tony could see that he was the man of her dreams."

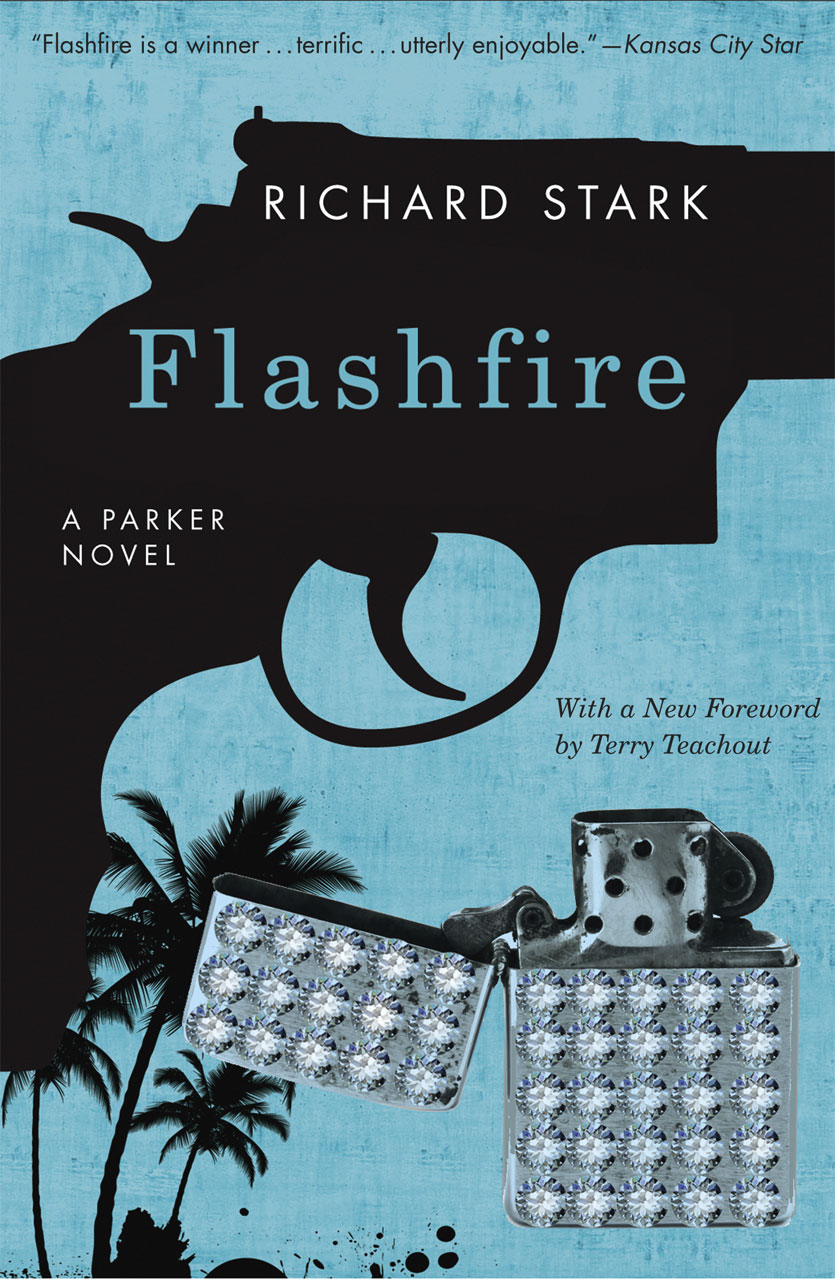

So, no head-hopping, right? Then what should we make of "Flashfire" by Richard Stark (pen name for Donald E. Westlake)?

So, no head-hopping, right? Then what should we make of "Flashfire" by Richard Stark (pen name for Donald E. Westlake)?I'm picking this book because, a) published in 2000, it's far from a hoary old holdover from a bygone age of letters, b) it's one of a very popular series by a very successful writer (more than a hundred books to his name(s), c) it was recently adapted into a major motion picture in Hollywood. And it has a HUGE chunk of head-hopping!

The main character, Parker, is smart, talented, and a crook: thief, killer, thug, plotter, and assassin. The book is all about his quest for revenge on some guys who cheated him on a job. Entertaining and fast moving, it's a good book, if you don't mind lots of guns, blood, heartless cruelty, and self-serving sociopathic criminality.

Anyway, the book uses a conventional first-person limited viewpoint. Parker knows what he knows and sees what he sees, but we don't get to know what other people are thinking or seeing... until Section Three (page 145 in the edition I read). At that point, the viewpoint comes unglued. We bounce around from one person to another, moving through past events and coming back to the present, being told straight out what people are thinking without circumlocutions like "He could see that the killer thought...".

First are the three guys who cheated Parker. Then we are in the head of the real estate agent. Then looking through the eyes of a right-wing anti-Zionist militiaman. Then inhabiting a rich old society belle of Palm Beach, FL (and, briefly, inside the mind of her latest arm-candy husband), before we jump to a state trooper. Curiously, the state trooper talks with Parker, but we are on the outside of Parker looking on, not inside Parker looking out as we had been for the first 144 pages.

After that, we tour around the heads of: the real estate agent (again), a different Palm Beach society lady, the real estate agent (again), the first society lady, the state trooper, the three guys who cheated Parker, still another society lady, the real estate agent, the arm-candy husband, the state trooper, the state trooper's wife, the real estate agent, all of the society ladies (each for about three lines), and we finish with the three cheating guys and the real estate agent (again!).

Finally, to start Section Four (page 227), we return to seeing the world through Parker's eyes, where the perspective stays for the rest of the book. That's about eighty pages of head-hopping, right in the middle of the novel. What gives? Why is this "rule" not just broken, but completely thrown out the window?

Because it's art and it's bloody brilliant, that's why.

On page 144, Parker was shot and left for dead in a ditch. When the head-hopping kicks in on the next page, the reader is dislocated from the main character and the main thread of the plot. In a masterful piece of writing, the viewpoint becoming detached from Parker echoes his three-quarters dead condition. We float from mind to mind like a disembodied spirit. Seeing, hearing and knowing things that Parker couldn't possibly see, hear or know.

Then, even as he comes out of his coma, we are still held at arm's length. It reinforces Parker's weakened state, as though he is battered down so far, he lacks the strength to even carry the narrative. Parker is carried along as a supporting character in various scenes, seen differently by different people as the perspectives shift. During one of the highest action sections of the entire novel, Parker is only along for the ride, not an active observer or participant in anything.

The entire structure of Section Three uses head-hopping as a meta-narrative device that not only throws Parker's weakness in high relief, it underscores his slowly returning strength when he once again takes up the narrative viewpoint in Section Four. He's still weak, but getting stronger. But is he strong enough to carry out his revenge?

It's a great piece of writing. As such, it shows just how useful and appropriate head-hopping can be when it's done right.

||| Comments are welcome |||

Help keep the words flowing.

I think the "head-hopping" advice is bogus as well (and I blogged as such a while back). As you point out, it can be excellent when it's done on purpose. I think the better advice would be, "don't head-hop by accident".

ReplyDeleteI think, as with all writing rules, it can be broken with magnificent results. But, of course, with the breaking of writing rules, the author better know the rule well, or it will come off as amateurish and prove again that the rule is there for a reason.

ReplyDeleteHead-hopping mostly confuses me, but sometimes not. Depends. I haven't read much of it and the first one, the lighthouse book by virgina woolfe, wasn't actually that confusing. Nora Roberts has a fair amount of head hopping in her books, too, but she's not that confusing either. (Her books are what make me wonder about the No Head-Hopping advice.)

ReplyDelete